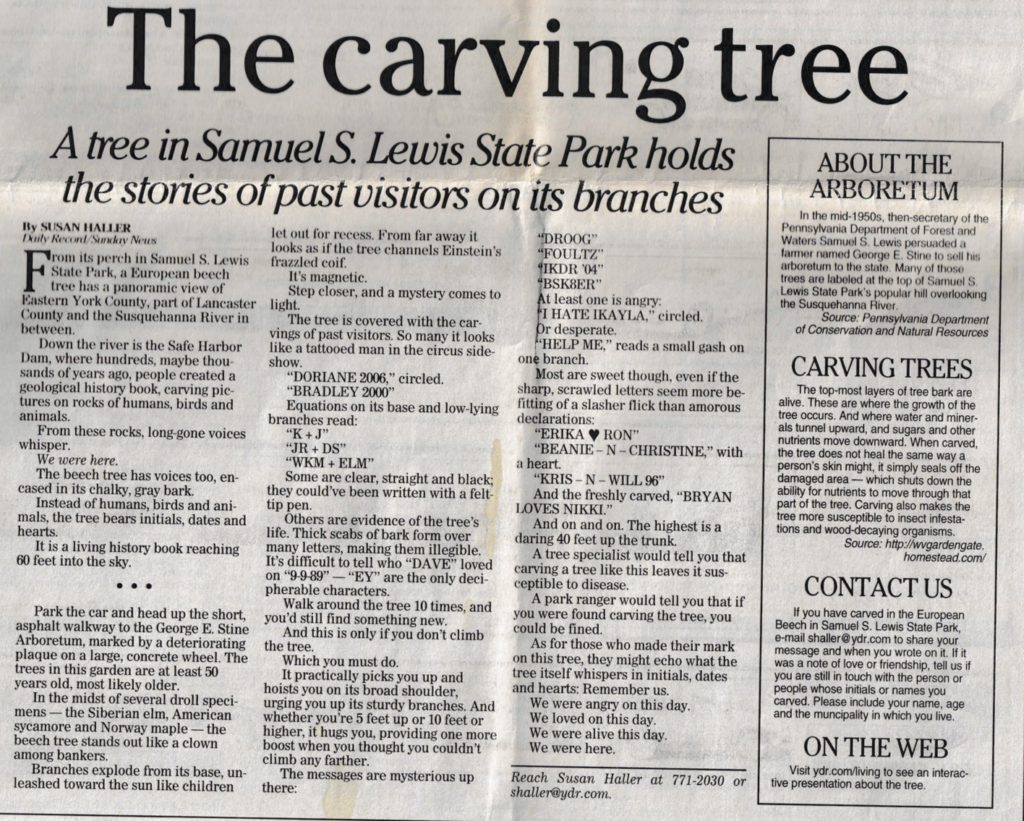

Years ago, back when I was an assistant features editor at the York Daily Record in York, Pa., I wrote a story about a tree.

From my editor’s perspective, I’m sure it was a less than exciting story pitch.

Me: So I was at Sam Lewis State Park this weekend and I found this really cool tree that’s completely covered in carvings. Can I write a story about it?

Editor: … You want to write a story … about a tree?

Me: It’s a really cool tree.

Editor: … You mentioned that. Will there be any cool humans to interview?

Me: I haven’t gotten that far. But trust me, the tree is really cool.

Editor: … If you want to work on it on your own time, go for it.

Typically, editors like to run articles about topics that are “newsworthy”- you know, stories that are timely and affect local people or stories that have an element of conflict or controversy– stories that are, you know, relevant to readers.

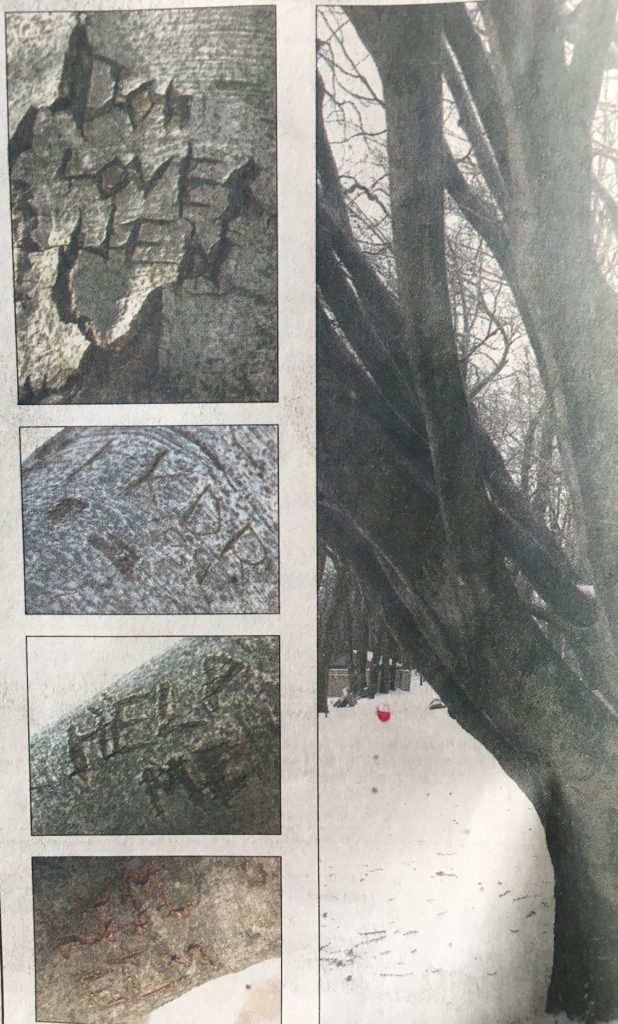

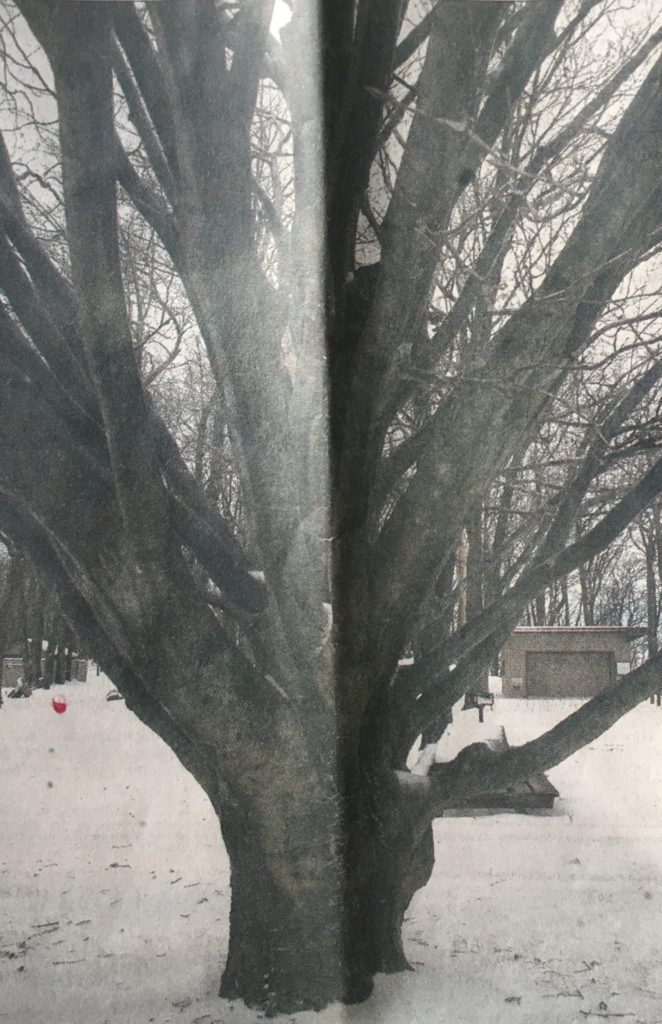

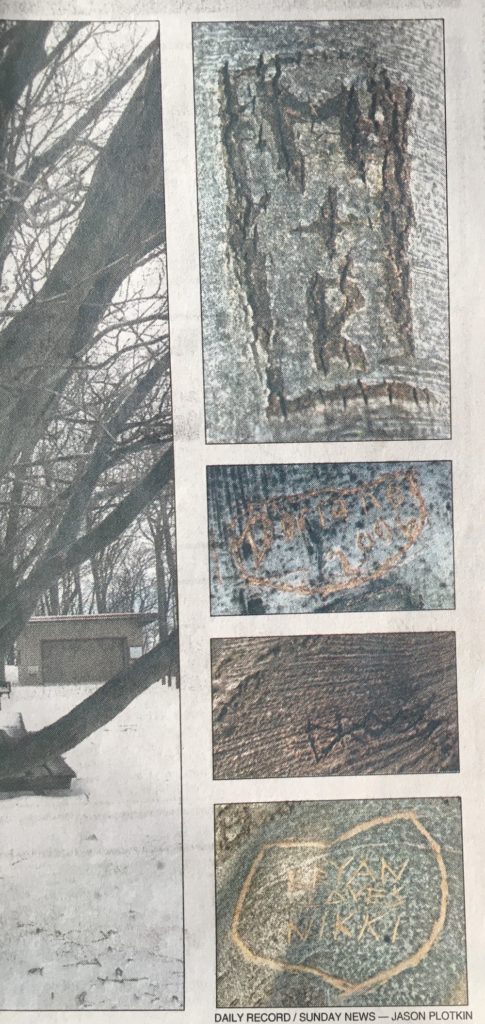

Random “cool tree” (which is truly just a subjective assessment by a tree-obsessed writer) at a local park really doesn’t tick any of those boxes. I mean the tree wasn’t new. It had been in that park for decades. It wasn’t an unusual species. It wasn’t the victim of a crime (though one could make the case that it had been physically assaulted hundreds of times by hundreds of lovelorn teenagers with Swiss Army knives) and it hadn’t committed any crimes. It wasn’t a celebrity or a politician. It had no special talents to speak of. It was just a big old tree in a park with lots of initials inscribed on it.

As an editor, I knew that. But as a tree-obsessed writer, I had this idea about it. I couldn’t just ignore the tree.

So I wrote about it.

And one of our photographers took pictures of it. And we made the story and photos a centerpiece in the features section. It was one of my favorite stories I’ve written. I thought I’d saved a copy of it back when it first ran in the paper- but during purging for multiple moves it went missing. And the online version is stuck in some inaccessible story archive somewhere on the inter webs. So I’d assumed it was just lost forever.

Until my personal archivist (i.e. Mom) showed up at my doorstep with a folder full of columns and stories I’d written in high school, college and after. And there it was! My story about the really cool tree. Thank goodness for Mom and her hoarding.

And I re-read it and I’m still proud of it. Though it’s not exactly timely. And there’s no real conflict or controversy. There are human voices in the story, though in sort of an abstract way. And it while it was a story about a local tree for a local paper, said local tree wasn’t involved in, like, rescuing puppies from a fire. It wasn’t running for mayor and it didn’t win the lottery. It’s not newsworthy maybe, but definitely story worthy. And I was just lucky enough to have a couple of editors who understood my vision (or, more likely, they needed to fill a news hole in a Friday paper).

For some reason, I thought about my tree and this story the other day while listening to Terry Gross interview Byran Stevenson, attorney, social justice advocate/warrior/evangelist and author of the memoir “Just Mercy” (I’m reading it now, it’s wonderful and thought provoking, add it to your list).

In it, he talked about visiting Johannesburg, South Africa, about the apartheid museum and the symbols, monuments and memorials that make sure people wouldn’t forget the injustices of apartheid. He talked about meeting Rawandans who want to ensure that no visitors leave the country without understanding genocide that occurred there. How their genocide museum has human skulls on display- a visceral showing of their grief. He talked about visiting Berlin and how he was practically tripping over markers that had been placed next to the homes of Jewish families who were victims of the holocaust.

These places with such horrific histories are begging for visitors to see what happened there. To look that atrocity and pain right in the eye. To confront it and then forge a path forward.

It’s something Stevenson said our country is in desperate need of. A reckoning with our ugly past– the sins of the genocide of indigenous people, slavery and Jim Crow. He’s working to correct that with the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum he’s opened in Montgomery, Alabama.

He illustrated the power of this reckoning with this really beautiful anecdote.

For the museum, people are going to the site of lynchings and collecting soil from the site in a jar. There are currently hundreds of jars of soil on display at the museum with the name of the lynching victim and the date of the lynching.

Stevenson told the story of a middle-aged black woman who went to a lynching site in a remote area to gather soil for the museum. He relayed how anxious she was about going, but how she did it anyway. At one point, she was digging and she saw a white man in a pickup truck. The truck slowed and the man stared at her. He drove by, then turned around and passed by again, slowly. The man staring at her as he passed. Then the truck stopped. And the man got out of his truck and approached her.

By now, Stevenson said, the woman was really nervous. The museum had instructed people who were collecting samples that they didn’t have to explain what they were doing. They could just say they were getting soil for her garden.

And that’s what the woman was planning to do, but when the man asked what she was doing, the woman said something got a hold of her.

“I turned to that man and I said, I’m digging soil because this is where a black man was lynched in 1931, and I’m going to honor his life.'”

Stevenson relayed how the woman was frightened and how she began digging faster. The man just stood there. Then he asked if the paper she was holding told the story of the lynching. It did. He asked to read it. She handed it to him. And he read it as she continued digging.

I’m going to quote Stevenson from the interview on the next part, because his description was so lovely and poetic:

“And then he put the paper down and stunned her by asking, would it be OK if I helped you? And then she told me that this white man got on his knees. And she offered him the little plow to dig the soil. And he said, no, no, no. You use that.

And he started throwing his hands into the soil with such force. And his hands were getting coated with this black soil. And they were turning black. And he was putting them in the jar. But he kept throwing his hands. And it moved her. And she said the next thing she knew, she had tears running down her face. And he stopped and he said, oh, I’m so sorry I’m upsetting you. And she said, no, no, no, no. You’re blessing me. And they kept putting the soil in the jar.

And they got the jar almost full. And she noticed toward the end that the man was slowing down and that his shoulders were shaking. And she turned and she looked. And she saw the man had tears running down his face, and she stopped. And she put her hand on this man’s shoulder. She said, are you all right? And that’s when the man said to her, he said, no. I’m just so worried that it might have been my grandparents that were involved in lynching this man. And she said, they both sat there with tears running down their face.

And at the end of it, he stood up and said, I want to take a picture of you holding the jar. And she said, I want to take a picture of you holding the jar. And they both took pictures holding the jar. And she brought this man back, and they put that jar on our exhibit together.”

So. I was listening to this. Wiping my tears. And my European Beech tree covered in decades worth of carving came to mind. And my editor came to mind.

I remember the conversation we had while working on the story. I was trying to tie together this idea of these ancient petroglyphs on boulders down river from the park with this tree and all it’s carvings. And I couldn’t quite articulate why it went together and why it mattered- only that I knew it went together and I knew it mattered.

And my editor said five words, “how about, ‘We were here’?”

As in, the reason for the petroglyphs and the reason for the carvings on the tree. Humans just want to leave their mark. To be remembered.

I could really use that editor right now. To help me tie together this tree and it’s carvings to the monuments in Johannesburg and the skulls in Rawanda and the markers in Berlin and the jars of soil in Montgomery.

I can’t quite articulate why they feel knitted together in my brain. It’s that drum that drum of human narrative still beating. All the time.

Not just “we were here.” But this happened. This happened here.

This awful thing happened here. Please see this awful thing here so that it does not happen again. Please remember the awful things done to our people. Please know that any awful things done to others are awful things done to ourselves.

My tree- it had stories. All those initials. I imagined most of them were love stories. But not all of them. I think some of them were desperate, scared, lonely stories.

As humans, sharing stories is in the marrow of our bones. They’re the delicate threads weaving us all together.

In an interview for OnBeing, poet Marilyn Nelson said as much:

“I know I feel, the older I grow, the more clearly I understand that that’s what we are, is our stories. That’s what we are. That’s all we are. We erase our stories, we erase our existence. And learning how to tell the stories, learning how to understand the stories, what they teach us and what they can teach other people, is really the essence of our existence here, I suspect.”

So here we are. Right now. In this place. In desperate need of telling the stories of what happened while we were here.

One of the most important lessons in life-changing storytelling I’ve learned as a writer, is that, you don’t get healing, you don’t get atonement, you don’t get grace, you don’t get forgiveness, you don’t get that beautiful story without first digging your hands deep into the ugly, shameful, horrific stories.

And I think that’s the work we need to do right now. Right now. That’s what we are here to do. We are here to tell the story of what happened.

Together, we reach deep into the soil of our collective pasts. Together, we lay roots for the redemptive stories of our future.

That’s what trees teach me. And stories.

We are here. This can happen here.