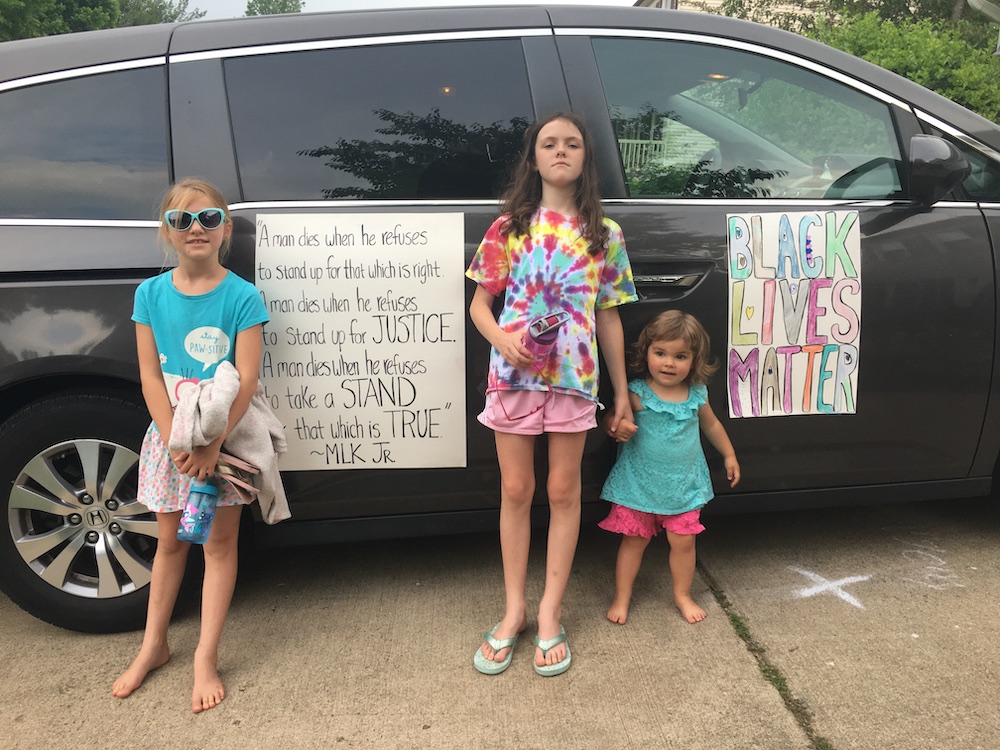

In the last week my family and I have participated in three demonstrations in support of Black Lives Matter.

On Thursday, a car rally through our town tucked in the sprawl of Washington, D.C.

On Saturday, a march to the greens in front of Town Hall.

On Sunday, a Kids Walk for Black Lives Matter in the most suburban fashion imaginable: Families parading down bike paths past strip malls, town homes and apartment complexes.

I’m sharing not to brag or pat myself on the back for any new-found “wokeness.” I am … we are… years … decades … centuries late to this protest.

I’m sharing in the hopes that another reader might see himself or herself in me – White, middle-aged, middle class suburbanite with three young kids- and realize that this is their fight, too.

I don’t generally like to be blunt or confrontational in this space. I’m the quintessential peacemaker/people pleaser. I know this about myself. I’m not necessarily proud of it. Because what that means, often, is having convictions and not speaking about them for fear of alienating, offending, angering or causing pain. While being a peacemaker/people pleaser can create peace for myself and please people and in my own small circle, it doesn’t do much to create peace in the broader context of humanity. If the only people who are pleased are the people who look and think like me, then I’ve only added more echoes to our echo chamber. I think it’s time to burst that bubble.

So here’s me being blunt: The fight against systemic racism in our country is not a black problem. It’s a white problem. It’s a problem white people created centuries ago by devising the concept of race in order to justify their enslavement and torture of black people. It’s a problem white people perpetuated by not enforcing the promises made in the 14th and 15th amendments. And it’s a problem white people continue to ignore and claim was already solved by things like the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s, by affirmative action and by the election of a black president. It’s a problem that we overlook and speak around in coded language because it’s inconvenient and uncomfortable and we’d rather not disrupt the status quo. And that’s the truth. Period. End sentence.

This is not an understanding I came to overnight. But rather a growing awareness I’ve built after years and years of reading essays, blog posts, newspaper articles, novels and books by black writers as well as listening to podcasts and interviews by and about race in America. Consuming stories and information from people who do not look like me.

I love this quote from writer Ta-Nehisi Coates speaking about white people needing to educate themselves about topics outside of their experiences/worldview/perspective:

“I don’t even think that’s a particular black thing, because if you’re black in this world, and you are gonna become educated on what is considered mainstream art in this world, mainstream traditions, nobody slows down for you. Nobody is gonna hold your hand and explain The Brady Bunch to you. Nobody’s gonna do that. Catch up.

Catch up. Some people live like this. I know it’s not what’s around you, but some people live like that. Catch up. And that’s just how it is. You gotta be bilingual. You gotta figure it out.”

You should probably just listen to the interview. It’s a good place to start this conversation. One stop of thousands in the journey to catching up. To becoming bilingual.

But if you’re reading and scratching your head and asking how black people’s pain is white people’s problem, why it has anything to do with you, just read this excerpt from “White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People to Talk About Racism” by Robin Diangelo:

“Consider any period in the past from the perspective of people of color: 246 years of brutal enslavement; the rape of black women for the pleasure of white men and to produce more enslaved workers; the selling off of black children; the attempted genocide of Indigenous people, Indian removal acts, and reservations; indentured servitude, lynching, and mob violence; sharecropping; Chinese exclusion laws; Japanese American internment; Jim Crow laws of mandatory segregation; black codes; bans on black jury service; bans on voting; imprisoning people for unpaid work; medical sterilization and experimentation; employment discrimination; educational discrimination; inferior schools; biased laws and policing practices; redlining and subprime mortgages; mass incarceration; racist media representations; cultural erasures, attacks, and mockery; and untold and perverted historical accounts, and you can see how a romanticized past is strictly a white construct.”

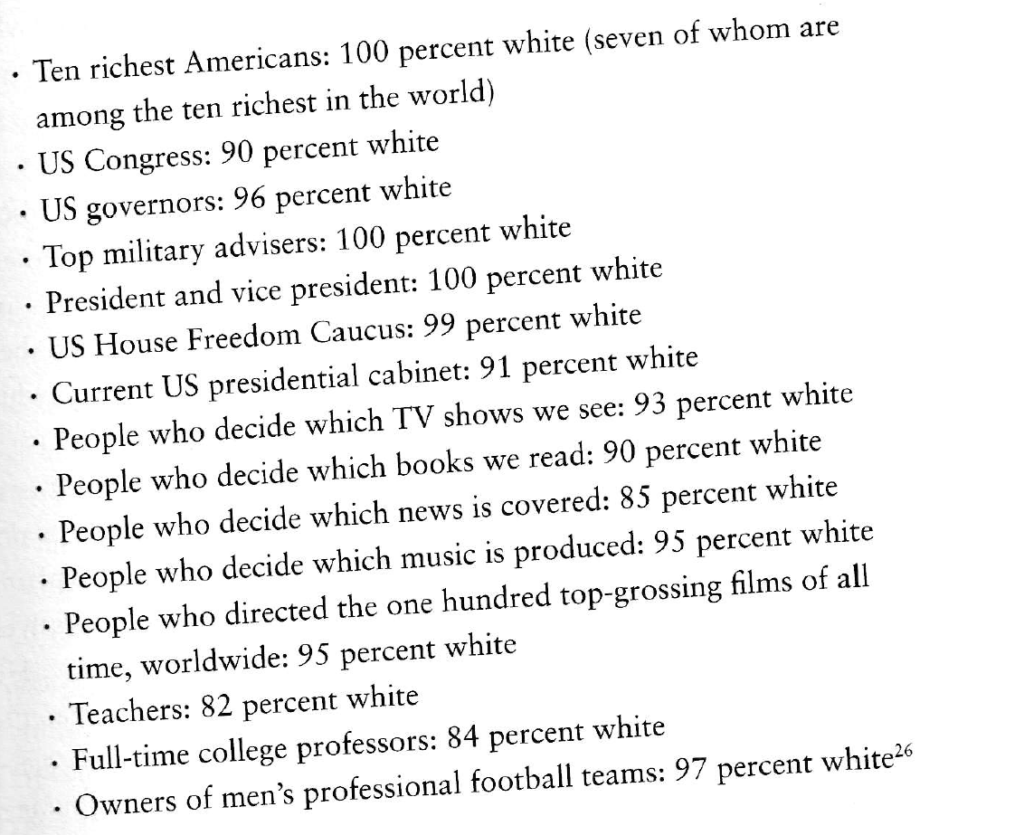

And Look at this list of the people who have power, make policy and make decisions in America then ask yourself, how is racial unrest in our country not a problem for white people to solve?

How is it on people of color? The descendants of people stolen from their homes and brought here against their will? How is it on the people who come here seeking refuge from oppressive regimes and violence or the opportunities promised by the American dream?

The last time I wrote about race was five years ago. And I felt apologetic about it then, too. But what I’m learning now is that white people should be talking about race. But we should be talking about it in the context of naming our own racist ideas, thinking and actions, and then sorting through how we came to have them and what we plan to do to eradicate them.

We should not be demanding that people of color teach us or tell us how to not be racist.

We should not be be attempting to lead or direct discussions that people of color have or want to have about race. And we shouldn’t be inserting ourselves and our guilt and our pain and our good intentions into those discussions. That is their sacred space.

We need to create our own sacred spaces to sort it out.

I just listened to this interview with trauma therapist and author Resmaa Menakem who talks about how the trauma white people have caused black people in our shared history is born out of the trauma that white people inflicted on the white bodies of themselves and each other during the dark ages- a thousand years of torture chambers, enslavement, land theft, genocide, colonialism, imperialism (is all of this sounding familiar?). Eventually those poor white people fled the oppression of wealthy white people, colonizing North and South America. Where they inflicted the same trauma done to them on to people of color.

“All of this stuff happened for a thousand years,” he said. “And then that body came here. This is why I say, white people, don’t look for a black guru. Don’t look for an Indigenous guru. Find other white people, and start creating a container by which you can begin to work race specifically; not race in this and race in that and break bread together and do all that — not that; not a book club. You specifically deal with the embodiment of race and the energy that’s stored with that.”

So that’s where I am. And that’s where we are.

Please know that I don’t believe I’m enlightened. I don’t believe reading some books or holding some signs up somehow liberates me from my own racism, prejudice or bias. I don’t have a large, diverse circle of friends. I have a small, white circle of friends offline and a broader white circle of friends online and sprinkled in there are a few black classmates and acquaintances. Ditto for other people of color. I’m not the embodiment of white antiracism.

I don’t believe that I know better than anyone. Or that I am better than anyone. Lord knows I have so much learning to do. So much learning. So much course correcting.

I’ve long relied on this blog as a place where I can sort through questions and discomforts. I’ve already drafted and not shared things I’ve written on this topic out of fear. I don’t want fear to continue to silence me. I don’t want the worry I have about saying the wrong things to stop me from saying anything at all. I know I’m going to get it wrong. But hopefully those errors will end up in growth and a deeper understanding.

In this conversation, I know I’ve already made mistakes.

Five years ago, in that post I wrote about race I said specifically, that addressing the problem of race in our country wasn’t my fight.

Which looking back, seems ignorant.

And, in the original post, I said something along the lines of, “all lives matter, but now it is especially important to remember that black lives matter.” Five years ago I felt that putting “all lives matter” softened my words in order to get my point across to potentially defensive readers. But for black people, the phrase “all lives matter” is hurtful and offensive. It’s a joke. How can “all lives matter” when it’s clear to them that black lives are so expendable?

What I understand now is that saying or writing “all lives matter” is a form of gaslighting. Discounting and ignoring black people’s lived experience. Patting them on the head and saying, “silly, you, everyone is important,” when all evidence of that points to the contrary.

I don’t know the exact wording of what I wrote in the original post because a while back, I went in and edited out the phrase “all lives matter.” Quietly erasing my ill-used good intentions. Like it never happened. Like I never wrote the words.

Only it did happen. And I did write the words. I did get it wrong. I know better now, but I never owned it until now.

I think about that as I watch all these monuments to Confederates being removed. Their removal from public spaces is certainly long overdue, but if we fail to reflect on why they were problematic in the first place and instead quietly go about our business like it never happened, well then we’d missed the point. And the opportunity to grow as people.

When I t think about the work that white people need to do to address race, it’s this sort of thing. This sort of uncomfortable, painful dissection and examination of our words and deeds and motivations.

My dad often talks about how really loving a person or people can mean that you have to have difficult conversations with them to help them grow. Well now is the time for that sort of love. He’d probably call it tough love, which doesn’t really sound like all that much fun. But if the end result of us having tough love for each other is that we’re able to literally save lives and mend the torn fabric our country was woven from, well then won’t that make it worth it? Isn’t the THE thing? The gift we pass on to our children and their children. We did the work now, so that hopefully our descendants don’t have to? They don’t have to continue making the same mistakes we made?

I don’t have assumptions about what’s on the hearts or minds of anyone who arrives on this page. Only what’s on my mind.

I know that when I marched over the weekend, that the chant “Black Lives Matter” transformed in my ears and my conscience. It’s not an affront. It’s not a claim to superiority. It’s not this incendiary phrase intended to anger people for the sake of angering people.

It’s a plea. People literally pleading for their lives.

When a black person says, “black lives matter,” they’re saying “my life matters.”

“My son’s life matters.”

“My daughter’s life matters.”

“My nephew’s life matters.”

“My niece’s life matters.”

“My uncle’s life matters.”

“My aunt’s life matters.”

“My friend’s life matters.”

When I marched this weekend I learned that the act of pleading for life and for justice is wearying. It literally strains your voice. When I considered how long people of color have been pleading, it occurred to me that their voices must be so tired by now. But still they’re pleading. Earnestly. Steadfastly. Loudly. Quietly. In whatever manner they’re able.

They can’t continue carrying the burden on their own. They shouldn’t have been carrying the burden alone for so long. We need to lend our voices.

When I marched this weekend, I learned that you don’t have to be a black person to raise your voice for the cause of black people. I learned that as a white woman, it feels awkward and uncomfortable to raise your voice and that the words “black lives matter” feel foreign in your mouth at first and like, they’re not your words to hold. But that it’s OK to say them. And the more you say them the more they become a part of your person. How they begin to cling on to your skin and sink down into your bloodstream and pump through your heart until you can’t imagine not saying them. You can’t imagine not shouting them.

When I marched this weekend, I learned that while it feels dire and dark, the unity and the gratitude shared in a community of marchers and a community of witnesses is palpable. It’s hearing the voices of people you can’t see joining in your chanting from front porches and balconies. It’s people honking their horns and raising their fists out of car windows. It’s thanking law enforcement for making it safe for you to march and hearing them thank you back for showing up. It’s hearing children raising their own small voices to call for justice.

It’s also witnessing the pain and the rage and the devastation etched into the faces and in the voices of the black people you’re marching with.

When I marched this weekend, I learned that eight minutes and forty-six seconds is a long time. I learned this while observing an eight minute and forty-six second moment of silence for George Floyd, who was murdered when a police officer casually kneeled on his neck for eight minutes and forty-six seconds. It’s a long time. As the sweat rolls down your forehead and mingles with tears and your knee aches from kneeling, and the quiet, save for the chirping birds, seems interminable.

When I marched this weekend, I felt something shifting in me. Something like resolve settling in. Something like the realization that the work I have to undertake for myself and for my family was going to be painful and marked by innumerable dead ends and pitfalls and wrong turns, but that I’d have to keep trudging on. Because it doesn’t get better if I stop. It doesn’t get better if I turn back.

There’s no going back now.

So let’s go forward.

Who’s coming, too?

There are a billion suggested reading lists by people who can speak more authoritatively on this topic than I can. That said, here are some books I’ve read that have helped open up my understanding of race:

Nonfiction:

- “How to Be an Antiracist” by Ibram X. Kendi

- “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness” by Michelle Alexander

- “White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People to Talk about Racism” by Robin Diangelo

- “Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body” by Roxane Gay

- “Between the World and Me” by Te-Nehisi Coates

- “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption” by Bryan Stevenson

- “The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace: A Brilliant Young Man Who Left Newark for the Ivy League” by Jeff Hobbs

- “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” by Rebecca Skloot

Fiction:

- “These Ghosts Are Family” by Maisy Card

- “Red at the Bone” by Jacqueline Woodson

- “The Mothers” by Brit Bennett

- “The Underground Railroad” By Colson Whitehead

- “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas

- “Beloved” by Toni Morrison

- “Americanah” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

- “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by Zora Neale Hurston

- The Known World” by Edward P. Jones

For more articles and podcast suggestions, visit this post.