For our 12th anniversary Brad got us tickets to visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture. This maybe seems like an odd anniversary present, but I was excited about it. I’ve been wanting to visit the museum since it opened in 2016, but between work, three kids and a global pandemic, I hadn’t found a way to make it happen. I hadn’t even realized the museum was open to visitors right now. Brad was dogged about snagging a pair of reserved-time passes on what ended up being a rainy Thursday

My grandmother and my parents had regularly taken us to the galleries and history museums that lined the National Mall all our lives. My siblings and I were lucky to grow up being able to hop on the Orange line and pop in to see the Hope diamond one day, Dorothy’s slippers the next and Alexander Calder’s mobiles on another. Museums were these wonderful places for discovery and art and culture.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that museums are sacred spaces, too. Places where the very best of human imagination, ingenuity and creativity can be found. And also the very worst.

In that spirit, I felt a deep sense of reverence upon entering the African American history museum. An overwhelming feeling of the sacred.

I had worried, on the days leading up to our visit, that my presence there as a white woman during such a fraught time in our nation’s reckoning with race would be, somehow, problematic. Or unwanted. That I was this interloper. And part of me felt that this was appropriate. It was not often as a white person in our country that I feel like the “other” or the “outsider.” The one who doesn’t belong. But this is an experience people of color feel daily when navigating the world. I could manage that feeling for a day at the museum.

But here’s where I was wrong. Here’s what was wonderful. I could walk through the exhibits as a white person in this museum of black history and still feel welcomed.

On the museum’s website, founding director Lonnie G. Bunch shares, “This Museum will tell the American story through the lens of African American history and culture. This is America’s Story and this museum is for all Americans.”

To be clear, it is not easy being a white person absorbing the story of African Americans through their lens. It is uncomfortable. It is heartbreaking. It is sickening. It is horrifying. But that’s as it should be, I think. Had I walked through exhibits that documented 246 years of slavery and another century of Jim Crow and segregation followed by decades of criminalization, prejudice and inequality and not felt horrified, then clearly I wasn’t paying attention. I wasn’t listening.

This had nothing to do with museum curators attempting to shame white patrons though. It wasn’t as if we were the dogs whose face was being shoved into the mess we left on the carpet. It was just as Mr. Bunch had described it. A history of black people on our continent, as seen through the eyes of black people. That it was so upsetting and shocking has more to do with the history I didn’t learn in my formative years than anything else. It was upsetting because I hadn’t seen this story told by this storyteller. And it was upsetting because of the urgency of the divide we are facing now as a country.

What the museum did, simply, was hold up a mirror. It was up to me to decide how I felt about what I saw.

Here’s what I saw. Walls covered in the names of hundreds and hundreds of ships delivering enslaved people to the Americas. The date each slips embarked. The number of enslaved people it carried at the start of the journey. The number who survived.

I saw a model of a slave ship filled with models of people lying on the floor of it.

“Do you know what this is?” I overheard a black man ask his black son, who was maybe 6 or 7. And then he told him.

I saw cowrie shells that were used to purchase humans. And cowrie shells that were carried as talismans. I saw iron shackles used to enslave men and women.

I saw whips. Long whips, that white men used on black bodies, but also smaller whips, that white women used on black bodies. I saw a rough-sewn feed sack with the following words embroidered on it:

“My great grandmother Rose mother of Ashley gave her this sack when she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her It be filled with my Love always she never saw her again Ashley is my grandmother — Ruth Middleton, 1921”

I saw a large stone auction block where black men, women and children stood as they were appraised like livestock. Where babies were ripped from the arms of their frantic mothers being sold away from one another.

I saw a large wooden bowl, carefully made and treasured, worn with time and use. Engravings on the edges with symbols from Ghana. A way of holding on to a land a person was stolen from.

I saw the hood of a member of the Ku Klux Klan, and I heard an older black woman explain to a black boy, “That’s what the people who killed us would wear.” The royal us.

I saw the names of 2,200 people who were known to have been lynched between 1882 and 1930.

I saw the metal bucket Martin Luther King Jr. soaked his feet in after his five-day march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

I saw a lot of documents. Remarkable, I thought, the power of all these pieces of paper. Paper documenting the cargo on a slave trip crossing the Atlantic. Paper containing the bill of sale for humans. Paper listing the estates of white men, including the names of the men and women they enslaved. Paper containing laws, amendments and legal proceedings used to justify and/or allow the ongoing ownership of other people.

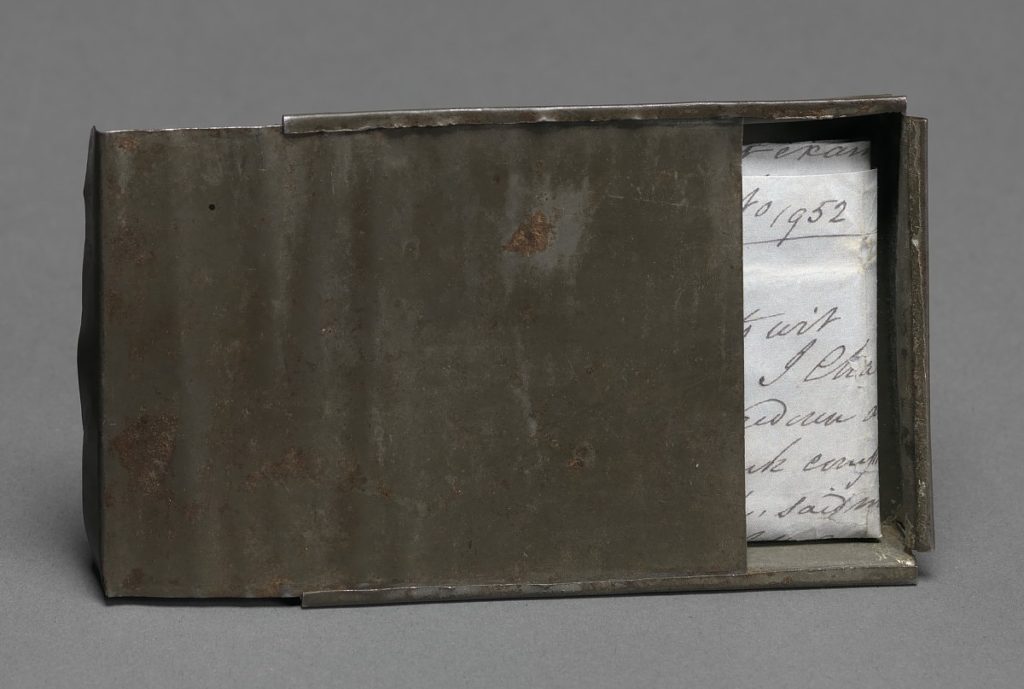

I saw a small tin box made specifically for holding a particular piece of paper. The paper declaring the maker of the box a free man. Papers he made sure to protect lest anyone challenge him on his status and re-enslave him.

Reflecting on the visit in my journal that night I wrote that I wanted to crawl out of my white skin.

The irony of this isn’t lost on me. That I would want to be rid of something that had been coveted for centuries. My white European roots. Would this museum have even existed if hundreds of years ago enterprising Europeans hadn’t invented the concept of race in order to justify enslavement? If they hadn’t posited that skin with less melanin is indicative of a superior sort of person than skin with more melanin?

Not that they knew what melanin was a back then.

How strange it is to want to disown the thing that makes my life easier. That lubricant of my movement through this world. To want to run from the thing that protects me. To run from it because of the way it shields me from injustice.

A friend of mine who works in academia posts regularly about white college professors who have been exposed for posing as a person of color, claiming culture and race that isn’t their’s in an effort to assimilate. I read those articles and think about how wrong these people are, how misguided to appropriate someone’s culture, to steal an identity. But I also understand what might drive someone to that place. Distancing yourself even a little from a culture you’ve learned has committed so many crimes against humanity. Claiming a place in a culture that’s been persecuted. Buying yourself some sympathy in the process, maybe.

I also understand the instinct to see the problem and then put my head back in the sand. To be so overwhelmed by the immensity and the darkness and the depth of the history that rather than face it, I curl up in a tight little ball and let it wash over me. Refusing to address it. That’s our flight instinct right? When faced adversity to run from it. Or hide from it.

And what about fighting? What does fighting look like? I think we’re seeing that now, too, right? How the words “systemic racism” evoke everything from skepticism to rage. How it immediately makes people defensive and indignant. How the very notion that white people might have advantages that people of color don’t has sparked a fire, causing people to take up arms and embrace conspiracy theories and what we thought had been fringe ideologies.

It is a false dichotomy, I think. That when faced with the mirror we can either fight or flee.

Just like the false dichotomy we’re being led to believe is the reality of being white it America right now. You can either be an ignorant redneck, gun-toting, anti-masking, Trump-flag-waving, right-wing conspiracy theorist who arms themselves in the name of Patriotism and preserving the American way or you can be a soft, gullible, lib-tard, progressive snowflake who spends too much time worrying about pronouns and white guilt and who hates police and loves socialism. That’s it. Pick your side.

Here’s the thing though. We know this isn’t true. We know there are more than two types of white people in our country. Despite what social media and comment threads and YouTube would lead us to believe, we know that we are a people capable of holding complex and sometimes contradictory ideas and attitudes together in one place. We can both support the second amendment and believe that Black Lives Matter. We can support the troops and support LGBTQ rights. We can take pride in our rural roots and care about the environment. We can be a lot of both-ands. We don’t have to be either-or. And we don’t have to assume everyone else is an either-or, either.

We know we are capable of holding bigger, broader ideas because we know ourselves as individuals can hold them. And we know we have family, friends, neighbors and co-workers who hold them. We know this.

And yet. Here we are. It would be naive to ignore the line that’s been drawn in the sand, too. Because there is undeniable division. It feels unfixable. Unbridgeable. And whatever chaos we’re marching toward seems inevitable.

It’s all grounded in fear, I think.

The division. It’s always been about fear.

In history class, I remember learning about Nat Turner’s rebellion. That’s it. I don’t remember learning about all the other uprisings of enslaved people. There were so many of them! Enslaved people fought back over and over. They weren’t resigned to slavery.

And that’s where the fear is rooted, right?

It’s the otherness of our different skin. The otherness of our different culture. Followed by the anxiety of uprising. The constant fear of uprising. The awareness that enslaved people with weapons would fight with justifiable fury. The understanding that those enslaved people outnumbered their white enslavers.

After Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676 when white indentured servants joined forces with enslaved and free Africans to fight on behalf of the rights of common people against wealthy colonists, the wealthy colonists worked to strengthen the American caste system. Fear of potential uprisings by marginalized Americans was used to further justify enslavement of Africans. And to sow seeds of divisions between what could have been useful alliances between white indentured servants and Africans.

These fears have continued to haunt American policy and legal decisions for hundreds of years. Fear that an American economy built on the backs of free labor couldn’t sustain itself after emancipation. Fear of a loss of wealth and prosperity. And maybe fear of the vengeance freed people might visit on their torturers.

Fear drove Jim Crow and decades of lynching. Fear drove red lining. Fear drives voter suppression. Fear drives mass incarceration. Fear drives police brutality.

Fear drives white supremacy. The idea that whiteness is somehow threatened by the existence of blackness and brownness. That there can’t be peaceful co-existence because we are too fundamentally different.

But all that’s a lie that fear tells us.

When you wander through the exhibits at the African American Museum of History and Culture, you see all manners of black and brown faces, doing both ordinary and extraordinary things. My favorite photographs were of regular people, living out their regular lives. So much of the black history we were exposed to in school was about hardship. Slavery and the civil rights movement. In American history, through the lens of whiteness, black people never got to be just regular citizens living out regular lives. We didn’t hear about how enslaved African Americans used to sneak off into the woods to dance or have church. We didn’t hear about all the businesses Black people started. We didn’t get to peek into their tidy living rooms to see their organs and their family portraits on display along with a photograph of Abraham Lincoln and rag doll or two made of brown cotton cloth.

The museum makes space for all of it though. After slavery, the history exhibit features this explosion of black life- both public and private. Joyful faces and serious faces at work, at school, at home, in town, on the farm, in all manners of life. From all walks of life. It was the American history I’d grown up with, but black-washed. And rather than feeling threatened by it, or that it was an afront to my whiteness or that it was a rewriting of history I felt immense gratitude. And love. That all this has been a part of our story this entire time and that I was finally able to see it.

The beautiful thing about the African American History Museum, is that it tells this rich, multi-dimensional story of black people. It’s not just the tragedy of Sally Hemings, the triumph of Martin Luther King and the talent of Michael Jordan. It’s this incredible tapestry of their perseverance, their faith, their dedication to human rights, their resolution and resiliency.

Their dignity. When faced with century after century of enslavement, torture, oppression, humiliation and imprisonment, they’ve made music, poetry and art. They’ve nurtured intense faith and launched movements- fighting against oppression and for equality.

And despite the righteous anger they could share with us as white people, they have opened their doors to us. To be a part in building the beloved community with them. They could meet us with bitterness. Instead, we’re welcomed onto the front porch. Invited to listen to a story. Despite the ugliness of our history, they’re still willing to reach out their hands so that we can all move forward together.

There was this quilt on display. Covered in the word “Freedom,” it was created by a woman who was fired from her job working in an elementary school cafeteria in Georgia for registering to vote. She took an injustice, and sewed affirmations for herself and for her fellow Americans.

That is what we’re being called to do. Confront ongoing injustice with ongoing reminders about the promise and possibility of our country.

When we take part in the liberation of Black people, we are taking part of the liberation of ourselves.

Here’s what the African American history museum taught me: That running from myself- from my European heritage, from my history, is a lost opportunity. Hiding from it, fighting it, these things will only prolong the pain. It’s leaving the bullet lodged in my shoulder for fear of the pain removing it might cause. It’s denying me the opportunity to fully participate in this gorgeous America we still today are building.

I think about what Civil Rights leader Ruby Sales shared:

“How do we raise people up from disposability to essentiality? And this goes beyond the question of race. What is it that public theology can say to the white person in Massachusetts who’s heroin-addicted, because they feel that their lives have no meaning because of the trickle-down impact of whiteness in the world today? What do you say to someone who has been told that their whole essence is whiteness and power and domination, and when that no longer exists, then they feel as if they are dying? … I don’t hear anyone speaking to the 45-year-old person in Appalachia who is dying of a young age, who feels like they’ve been eradicated, because whiteness is so much smaller today than it was yesterday. Where is the theology that redefines for them what it means to be fully human? I don’t hear any of that coming out of anyplace today. There’s a spiritual crisis in white America. It’s a crisis of meaning. We talk a lot about black theologies, but I want a liberating white theology. I want a theology that speaks to Appalachia. I want a theology that begins to deepen people’s understanding about their capacity to live fully human lives and to touch the goodness inside of them, rather than call upon the part of themselves that’s not relational. Because there’s nothing wrong with being European-American. That’s not the problem. It’s how you actualize that history and how you actualize that reality. It’s almost like white people don’t believe that other white people are worthy of being redeemed.”

I believe white people are worthy of being redeemed. I’m not speaking about a particular white person who doesn’t hold the same political beliefs I do. I mean white people as a collective. The whole of us carrying the burden of our forefathers racism and the weight of our inherited prejudice. What the last six months have shown me is that it’s essential that we can look ourselves in the mirror and choose to love what is reflected back at us. Both the ugly parts and the beautiful parts. We have to embrace the whole of it in order to move forward. We have to see each other. Really see each other beyond geography, ideology, education and upbringing. As human beings.

I saw this quote from Nayyirah Waheed referenced in “Here For It” by R. Eric Thomas. Waheed says, “If someone does not want me, it is not the end of the world. But if I do not want me, the world is nothing but endings.”

I have these beautiful little white daughters who I love fiercely. I don’t want to transfer the bullet to them- though I’m sure I’ve already shared fragments of it. I want for them the peace of inclusion. Of equity. Of real love for all the people in all the colors. That’s where we find peace as a nation. That’s where we find our beginnings.

While Bill Bryson was preparing to write his book The Body…..he observed a professor/surgeon dissect a cadaver. The professor gently incised and peeled back a sliver of skin about a millimeter thick from the arm,. Bryson describes the sliver of skin as being so thin it was translucent.

The professor’s comment was : “that is all your skin color is—that is all race is —a sliver of epidermis.”

Soon afterwards speaking to someone at Penn State who gave a nod of assent to Bryson’s sharing with her what he learned at the dissection. She commented:

“ It is extraordinary how such a small facet of our composition is given to such importance.” “People act as if skin color is a determinant character when all it is is a reaction to sunlight.” “Biologically there Is actually no such thing as race…nothing in terms of skin color, facial features ….or anything else is a defining quality among peoples and yet look how many people have been enslaved, hated, lynched or deprived of fundamental rights through history because of the color of their skin.”