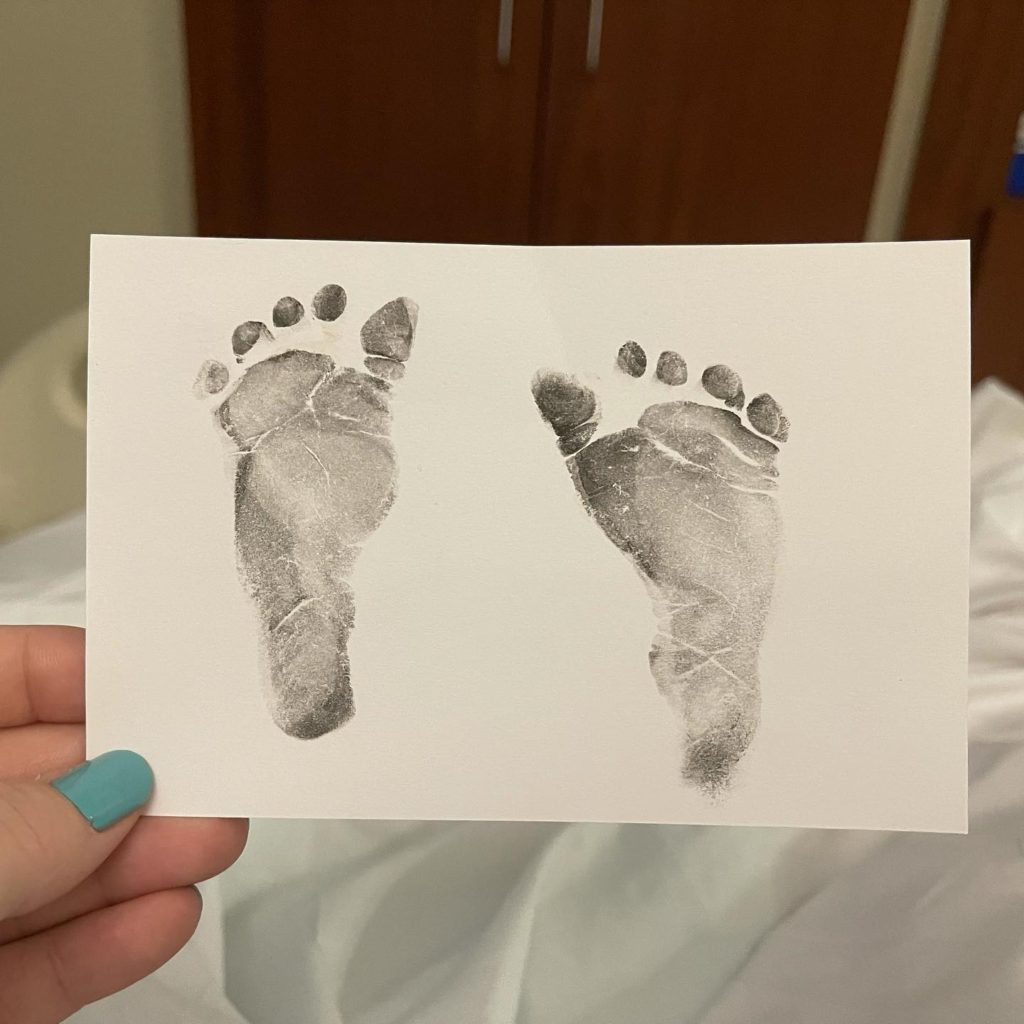

My niece, my practice baby, just had a baby of her own in October. My great nephew is, by my estimation, perfect. His mother thinks so, too, though she notes he is colicky from 5 to 9 p.m. (or 10 or 11) every night. Sometimes it starts earlier. Sometimes it goes later. And that he doesn’t prefer to be put down. Ever. So her to-do list is perpetually long.

She reports all this on a video message while pacing around her house, her son’s head tucked under her chin. I watch the video and the hollow space under my chin, just over my throat flushes. I can feel the warmth of a newborn’s head there. The softness of her hair. The god in those tender moments where two beings who had been cleaved at birth, suddenly fit back together again just so.

As she does laps around the house, my niece tells me she returns to work in nine days. Just 12 weeks after she delivery by C-section. She sighs a lot in this part. Her face is drained.

“I have a lot of anxiety about him going to daycare – completely irrational anxiety,” she says. “In my brain, my brain tells me ‘oh, he’s going to daycare, he’s going to die.’ It’s a stupid anxiety and I know it’s unfounded, which makes it even more maddening.”

As I’m listening to her, I feel my chest tighten. I grit my teeth. My eyes begin to pool. I remember this feeling. I remember this so clearly.

Almost 12 years ago this was me. And the baby was Lily. And I was pacing my house in tears counting down the days until the end of my 11-week maternity leave. Each day gone, I felt more anxious. More heartbroken. I cried and prayed for a solution. I did not want to leave Lily at daycare. I was desperate not to leave her at daycare. That I should be the one tending to my tiny infant daughter was a rare moment of crystalline truth for me.

But my leave ended and the grandparents had to go home. And so Lily had to go to daycare. That first drop off was awful. Somehow the precious few ounces of breast milk I’d packed for her had spilled all over the diaper bag. I had tried to pump during my leave to stock up, but struggled to express much milk at all. On that first day we’d already need the formula I’d purchased “for emergencies.” I remember floundering to clean up the milk. I remember setting her in an infant swing. She was so tiny. I remember kissing her little head. And walking out. And crying all the way to work. And snuffling at my desk the entire day. Having someone suggest I avoid looking at pictures of her, because it only made the feeling worse. It was traumatic.

When I look back at that time- those days leading up to daycare dropoff, that first day- my body tenses. It remembers.

The drop offs became more routine, but never felt right to me. The women caring for Lily were kind and gentle and she seemed to adjust to the new routine without issue, but I hated it. I hated missing her all day. Not being the one to feed her and change her and rock her. I hated ducking into a conference room twice a day and praying that the locks were working to pump. I hated the panic of sitting in traffic, knowing I had minutes to get to her before daycare closed. I hated the rush of preparing dinner and getting her ready for bed.

Our whole lives felt like a machine. All these tightly fitted gears moving in a specific order day in and day out. There was no spaciousness. No chance to breathe. No time for really knowing each other. Lily growing and changing so quickly. Being so little and sleeping so erratically. My own body still recovering. My brain cells recalibrating to adjust to this new role as a mother. This new reality.

I loved my job, but I knew I couldn’t stay. I needed to be with my baby. A few months after that first drop off, gave my notice at work and picked up Lily from daycare for the last time. I’ve never regretted that decision. Freelancing created a whole new set of stress and there were always financial worries, but they paled in comparison to the pain I’d felt being separated from Lily.

As my niece talks about her “irrational anxiety” about daycare, I feel my stomach start to boil.

“Not again,” I think. “Not to her, too.” and I’m angry at myself for not changing the world for my niece. And I’m angry at the world for not valuing mothers in any meaningful way.

I’m angry that my niece, at just 25, believes her fears about leaving her child are irrational. Silly and unwarranted. The product of brain dysfunction. Instead of what it actually is: Societal dysfunction. How thoroughly women absorb the message that we are not to trust our own knowing.

I drank from the well of my own self-doubt for decades. I still do. Why should I trust my gut, when all outward evidence from the world around me told me what was normal: Women have babies and after about 3 months, women find care for those babies, and obligingly juggle careers, child rearing, and homemaking without complaint and while making it appear effortless.

I knew this was the case because there were at least three women who delivered babies at my work the same year I had Lily. And we all followed these same steps. Sure, we’d check in with each other from time to time about how it was going. We’d grimace and say without saying that it was all “OK” (when in reality it was not). That we were just sleep deprived or hormonal. That this was just all part of the unspoken contract we’d signed without realizing it the second we entertained the idea of raising children in the U.S..

I need to state this for the record. For anyone who is reading or just to scream it into the void: THIS IS NOT OK.

My niece’s “irrational anxiety” is actually just instinct. It’s the primal part of her that knows it is too soon for her to separate from her newborn. It’s not unfounded fear. It’s the knowing under the knowing. The data that digs deeper than the medical chart stating her body has healed enough to return to work and of the vaccine record saying her newborn is safeguarded.

In all likelihood, her baby will be fine. And she’ll muddle through. But there’s nothing OK about it. Nothing fine.

It’s cruel what we do to new mothers as a country. The only policy brushing against maternity leave in our country is the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) which guarantees 12 weeks of unpaid leave during which your job should be protected.

The American Academy of Pediatrics endorses a minimum of 12 weeks of paid parental leave.

“Frankly, if I were to suggest it, I’d say six to nine months should be the minimum. I know we’re so far away from that, that it’s hard to even speak about, but by six months the parent is really in a different place with their child. Leaving them part of the day and finding child care is also easier at that point,” said Dr. Benard Dreyer, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at the New York University School of Medicine and past president of the AAP during a 2016 interview.

I can attest to this. Dropping Annie off at daycare for the first time when she was just over a year old was vastly different than dropping off 12-week-old Lily. Annie was sturdier, walking, eating solid foods. I was done breastfeeding, mentally sound, and ready to go back to working full time.

According to the AAP, “Research in high-income countries shows that prolonged paid parental leave is associated with higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding, on-time immunizations and decreases in neonatal mortality.”

With Lily, I was lucky enough to have a job where I could stockpile my vacation days and then use short-term disability to cobble together a maternity leave that didn’t leave us too financially strapped. Brad used some vacation time, too. But many parents don’t have access to any paid leave and can’t afford to take unpaid leave. So they take off as few as 6 weeks. Just long enough for a doctor to sign off that their bodies have healed. Six weeks is also, coincidentally, the minimum age an infant can start daycare.

So here is this new mother, physically able to work according to her doctor- still surging with hormones and sleep deprived and recovering from what is arguably the single most impactful event of a human life (excepting for maybe their own birth and death). And here is this new baby, tiny, fragile, tender, and totally beholden to others for all his wants and needs separated from the people who know him best.

To be clear: I am not judging my niece for sending her child to daycare. There is no judgment toward any parent making difficult decisions on behalf of their children. Whether that’s going back to work at 6 weeks or 12 weeks or a year or not at all. There are no easy answers here.

And there’s no judgment, either, for the mothers who are eager to return to work and who might welcome the end of their leave and the break from diapers and bottles. No judgment really, truely. We are a better country when we are able to take the path that sings to us rather than get in line behind what we’re told to accept.

What I’m saying here is that the anxiety my niece feels is not OK. Her body is telling her she is not ready to return to work. Her subconscious is telling her she’s not ready to leave her baby yet.

She’s waging a mental war against society’s expectations and society is winning. It’s telling her she’s crazy.

She is not.

What I am judging is that as a country we train women to believe that their valid fears are irrational because it’s inconvenient for them to believe otherwise. We ask them to ignore their instinct for the sake of business as usual. We ask them to sacrifice the most precious, critical months of their and their child’s life for the sake of business as usual. We ask them to ignore their mental and physical health for the sake of business as usual.

It’s not OK.

I’m judging the fact that, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, just 20 percent of employees in the private sector had access to paid family leave. And that just 8 percent of workers who earn the least – under $14 an hour- had access to paid leave. I’m judging the fact that Black and Hispanic Americans are less likely to have access to paid leave than their white counterparts.

It’s not OK.

My niece is her family’s primary breadwinner. Just three months after having a baby, she is talking about having to get up at 4 a.m. to get herself and her baby ready for the day so that she can get to her job as a nurse on time. Her husband just started a new job and has no leave. There is no wiggle room.

In her message, my niece mentions that during her post-partum check-up a questionnaire she filled out indicated she had post-partum depression.

And my niece, always practical, just shrugs. What was she to do about any of it? Take the prescribed antidepressant. Game plan the places at work she might be able to pump (there’s a shower stall currently being used for storage that might do the trick). Do some dry runs of the new morning routine before she jumps into life as a working mom. (I suppose her husband is now a working dad, but that’s not a phrase we ever use).

Because that’s what women do. Swallow the pain. Dive headfirst into the absurdity.

The thought of my three girls having to do the same makes me livid. Hysterical. Makes me want to be high maintenance, bitchy, bossy, shrill. Enough is enough.

It’s not OK.