Note: I wrote this post three years ago, but never published it out of fear about how readers close to home might react. Rosalinda is featured on our family Christmas card though – so it’s time to share the story behind her … makeover.

Here goes:

One Christmas when I was in late high school or early college, my parents gifted me an antique doll. She was the size of a 3 year old and wore a heavy, ivory-colored dress trimmed in lace with a matching bonnet. Her hair was wheat colored, wavy and matted. Her head was ceramic. She had round, blushing cheeks and a small rosebud mouth that opened just a little exposing a row of tiny clay teeth. Her eyes were a wide glassy brown fringed with delicate, hand painted eyelashes and full eyebrows.

“She was made in the 1920s,” I remember my dad telling me. “Her hair is made from real animal hair.” He handed me a printout with information about the dollmaker: a German manufacturer called Heinrich Handwerck, which produced dolls with bisque heads and composition bodies between 1876 and 1932.

“She was not inexpensive,” he added.

I remember not wanting to breathe on her. Or even touch her really, for fear that even the smallest jostle would result in a lost limb or a cracked skull.

Dad, who is a woodworker, ensured she would be protected. He built a beautiful glass-sided display case for her and made a pedestal table for the case to sit on.

At the time, I remember thinking that a toddler-sized antique doll seemed like an odd gift for someone just entering adulthood.

As a child, it was magical to peel back the crisp tissue paper of a pastel-colored box and find a porcelain doll with glossy hair in perfect ringlets wearing lace and satin-trimmed dresses. But by the time I reached high school, the collection of dolls my parents had given me on childhood Christmases was gathering dust and cobwebs on another shelf my dad had made in my childhood bedroom. Opening one last doll at 18 or 19 was different. A reminder of a person I had been, but was no longer. It felt like a shrine to a childhood that stretched back even before my own childhood. A bit of nostalgia to be looked at, but not touched. Admired, but not disturbed. Preserved as an ideal.

I saw the doll through my dad’s eyes. A treasure. The work of a craftsman. A toy so well built it survived decades. Something of much greater value than the plastic Barbie dolls we’d played with incessantly or the plastic American Girl Dolls we’d always coveted but never owned. I was old enough now to appreciate the doll in a way I never could’ve as a child. By gifting this particular doll- this valuable antique- maybe my dad was walking the fine line between my childhood and my impending adulthood. With this doll, I could be both the little girl who played with toys and the grown woman who could appreciate a relic of a bygone time.

But, of course, I saw the doll through my eyes, too. She was old, bulky, and required such care. She made me sad. Because I knew I would never look at her with the same adoration my 9-year-old self might have looked at her. I wasn’t a kid anymore. And anyway, antique dolls with their steady stares and their frozen formaldehyde faces were unsettling. She was stuffy and stern and smelled like mothballs. My life was just starting to take flight and she felt like an anchor.

For years, she lived in the upstairs hallway at my parents’ house. The apartments I lived in during college and just after were small and not suited to her. When my parents sold their house and moved West, the doll finally came to live with Brad and me in our first home.

She occupied a corner of the finished basement, regularly scaring the woman who checked on our cats when we went out of town. Overnight guests who stayed downstairs always requested she be covered with a sheet. Just so she couldn’t watch them while they slept.

One friend’s daughter, who was 3 or 4 at the time, kindly requested that “the weird, small person” be stowed away when she came to visit.

Everyone who knew of her speculated that she was haunted. “You better be careful,” they’d tell me. “That creepy doll will probably murder you in your sleep one night.”

Maybe it was because I grew up under the watchful eyes of multiple now, admittedly creepy dolls, I wasn’t particularly concerned about this doll. I never sensed any bad omens from her. But just the same, I found myself greeting her when I’d pass her in the basement. And being careful not to say anything disparaging or judgmental around her. You know, just in case. I didn’t want the girls to worry that she could potentially come alive at night and lurk around corners plotting to cut off their hair with butcher knives or decapitate our cats or whatever it is creepy dolls are wont to do. I told them she was a gift from Papa, and that she was fragile and beautiful and that they could look at her but couldn’t play with her.

When we moved to Virginia five years ago, we no longer had a basement to store the doll in, so she moved into another upstairs hallway.

And then something sort of magical happened. (Not magic, like, we’d mysteriously find her standing at the foots of our beds magic). But she did come alive in a way.

At this point, the doll had acquired a following of sorts – mainly friends who’d inquire if we still had her and if we’d observed her eating the hearts of small mammals on full moons. She regularly came up in Slack conversations between Brad and his co-workers. We decided that now that she was more of a daily part of our lives, hanging outside the girls’ bedrooms, that she needed a name.

Jovie suggested Rosalinda. And that was pretty much perfect. So we named her Rosalinda.

We decided that Rosalinda might be lonely in her case all by herself, so we dug out the bedraggled stuffed cat that Brad had since he was a child and gave her a friend.

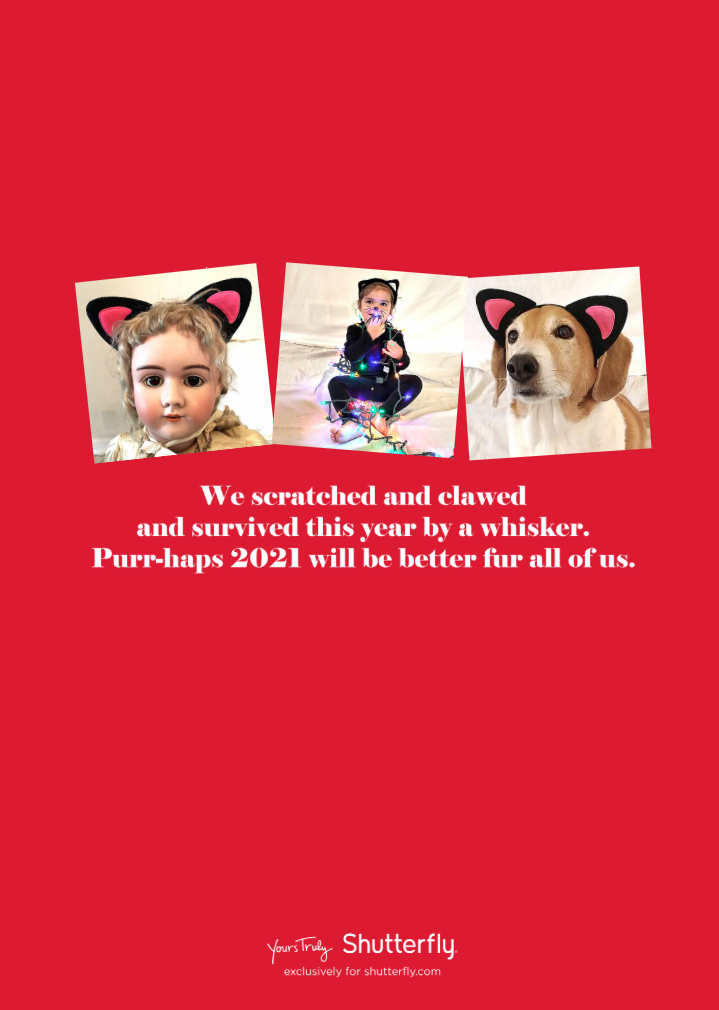

We included Rosalinda in Christmas cards and set her up in the front window on Halloween to greet trick-or-treaters. During virtual school last year, Rosalinda could periodically be found hanging out in the background of my classes.

Rosalinda seemed to invite other misfits and misunderstood objects to our home – like yoga frog, which showed up under our cherry tree a couple years ago and “Dat,” (as in when Annie asked, “what is dat?”) of the Indonesian Stick Puppet we found on our front stoop one day.

Rosalinda went from being this fussy antique to being a valued member of our family. We all delighted in and celebrated her.

I wanted to share unique gifts with more people in our community.

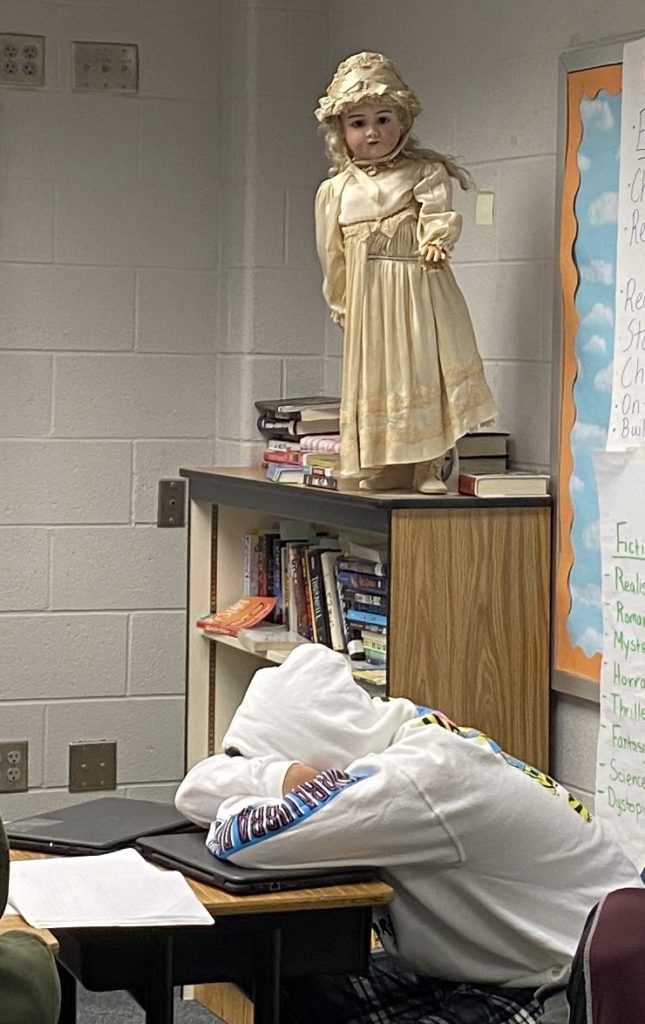

So when Halloween rolled around this year, I decided I would bring Rosalinda to middle school.

Now, before you yell at me for needlessly scaring a bunch of already anxious, exhausted adolescents, and for bringing a valuable, but slightly terrifying antique into the melee of middle school, hear me out.

It has been a really challenging school year. Not only because I’m a first-year teacher, but also because most of our students hadn’t seen the inside of a school building in 18 months. Let me tell you, after a year and a half of doing school in their pajamas from the comfort of their beds with ample access to snacks, Tikstagrams, InstaSnaps, FaceTubes, and what all, they have not been eager to sit in hard, plastic classroom chairs at 7:30 a.m. to learn about bias or theme or conflict from an overeager middle-aged lady. At the beginning of the day, they’re barely conscious. At the end of the day, they’re rattling the walls counting down the seconds until the bell rings.

They tell me they hate reading. They tell me they hate writing. As these are the fundamental components of most English classes, every day is a struggle. I liken teaching English this year to trying to feed rice cereal to a 6-month-old. You sneak a little spoonful of learning in, only to have them shove it out with their tongues and send it dribbling down their faces.

I needed some sweet potato or mashed bananas to catch their attention.

Cue Rosalinda. Weird, unsettling Rosalinda with her fussy satin gown and dead stare.

Ahead of our short story unit, I thought Rosalinda could serve as inspiration for a writing exercise. I would introduce her to my classes and they would write a response to the prompt “What did Rosalinda do last night?”

And maybe, just maybe, our reluctant writers might be willing to write … something … anything.

So a few days ahead of Halloween, I carefully rolled Rosalinda up in a blanket and stowed her in a duffle bag, which, admittedly, looked liked Lands’ Ends’ version of a body bag. At the start of second period, my co-teacher and I greeted the students and I introduced our special guest.

The kids, who are generally catatonic, perked up. And, as I’d hoped, the comments began rolling in. “That doll is creepy.” “Yo, that doll looks like it will kill you in your sleep” or the student who took one look at her and said, “nope” and buried his head in his sleeve.

We prompted the kids to write something, anything about the doll. And a small miracle occurred. Many of them picked up their pencils and wrote. Some of them described how she looked and came up with a backstory. And, predictably, many of them came up with wild scenarios of Rosalinda on murderous rampages and surviving apocalyptic revenge plots. If nothing else, Rosalinda’s presence offered some levity (or maybe terror?) on an otherwise ordinary school day.

Success, I thought to myself. A small win. I couldn’t wait for our 8th period class- one of my most spirited- to see her.

Before fourth period, I covered Rosalinda with a blanket as to not alarm my co-teacher’s advisory class, and headed next door to my other classroom.

And then, tragedy.

After fourth, my co-teacher rushed into my room, “Susan,” she said, her eyes full of worry, “Rosalinda broke!”

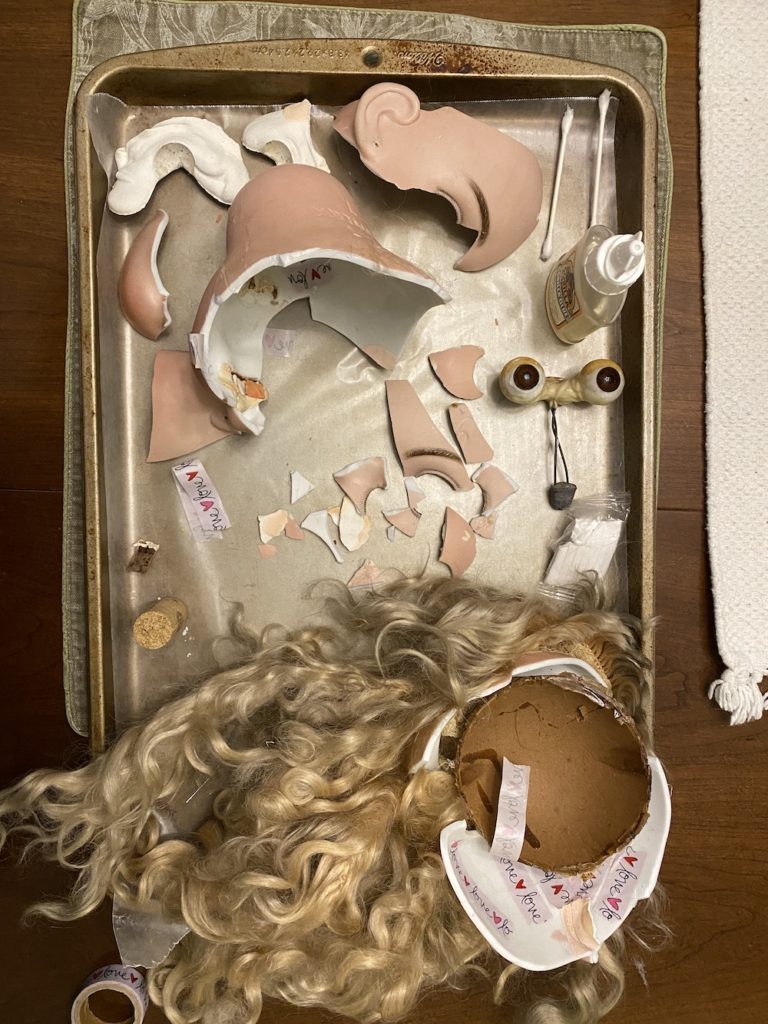

I went back next door where Rosalinda’s head was spread out on the carpet in what seemed like a thousand pieces. My co-teacher was apologetic as she explained that one of her students had wanted to see what was under the blanket and when they uncovered the doll, she fell off the chair I’d set her on …

I stopped listening as I looked at all the pieces. The panic sinking in.

“I’m an idiot,” I thought to myself. “I never should’ve brought her here.”

“It’s OK,” I told my co-teacher. “It’s not your fault. I should’ve taken her back to my room with me.” I grabbed the duffle bag and we began picking up pieces of the doll, stowing them in a zippered pocket. My co-teacher offered to pay for repairs, she apologized over and over. I told here not to worry. “It’s just a doll,” I told her. “It’s just a thing. It’s OK.”

It was worse somehow thinking of her taking on the guilt of this broken doll, when it was my choice to bring her. My choice to leave her on the chair. My choice to cover her up.

“Dad can’t find out,” I told myself. I could picture his disappointed face. I was a child again. I was irresponsible and careless. I clearly wasn’t ready for nice things.

Things had felt strained with him over the past couple years, like we couldn’t quite get in step with one another, like we we were forever tripping over each other’s worldviews and ideals. At times, the wounds have felt too gaping to heal. This was just one more thing.

I stowed Rosalinda’s body back in the bag and put it in the trunk of my car. The tears sprung out of my eyes, but I willed them to stop. There was not time for it now. I was so angry at myself. Angry at the building and a school year that I felt kept taking from me. Kept making me feel like an incompetent failure. Here was more confirmation.

Jovie was distraught when I told her. “I kept thinking you shouldn’t bring her,” she said sobbing. “I was worried something would happen to her. Can we fix her?”

And I shook my head. There were just too many pieces. She was too broken.

The duffle bag sat outside my closet for weeks. I pushed it aside when I needed clothes or shoes. I couldn’t look at it. Every time I saw it, bitterness bubbled under my skin.

On the day Rosalinda fell, I texted my sisters about it. “I’m devastated,” I told them, knowing it was silly to be so sad over a toy. But my sisters understood. Rosalinda wasn’t just a thing we kept at the top of the stairs. She had become part of our family lore, one of my sisters told me. She was woven into my story, into our story. Her fall was a small death.

Each time she looked at the duffle bag, Jovie would ask what I was going to do with the doll. “Are you sure you can’t fix her?” she asked. And I just shook my head.

Late in November, tired of tripping over the duffle bag, I finally decided I needed to figure out what to do with Rosalinda. Her body was in tact and undamaged. Just headless. I returned it to her case at the top of the stairs, because I didn’t know where else to put it. I took a deep breath and unzipped the pocket with all the fractured pieces. There were so many of them. I picked up the largest pieces and studied them. I began to see how they fit into each other. I grabbed a box and put all the pieces in the box. Then onto a wax-paper-lined cookie sheet.

“You’re putting her back together?!” Jovie was eager. Her eyes hopeful.

“I don’t know. I’m going to see what I can do.”

She looked relieved. “I was worried you were going to throw her away.”

I sighed. I was not as hopeful. After the past couple years, its outrages, disappointments, tragedies and losses, hope felt like a sentiment only meant for children. Impractical and impossible and impermanent.

“I’m not sure it will work. But I will try.”

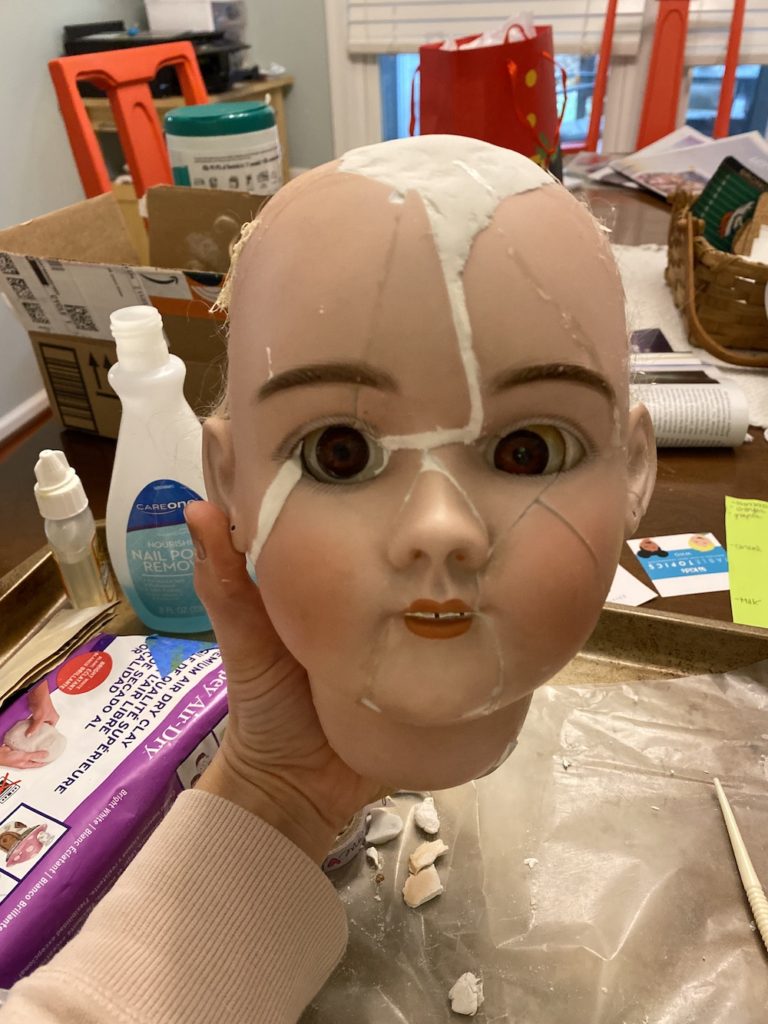

And I tried. It started with a line of Gorilla glue and a couple pieces of Washi tape. And time. I glued two pieces together and waited a day. And then added another piece. And waited another day. I stowed the cookie tray on top of the refrigerator, taking it down a few times a week to fit another piece here or another piece there.

Some of them went together seamlessly. Most of them didn’t. The further along I got, the trickier the pieces became to wedge together. I bought some air dry clay and used it to help fill in cracks and big gaps. At one point one of her glass eyes cracked and had to be reconstructed. Then I had to figure out how to re-attach the eyes to the head. Then I had to figure out how to reattach the reconstructed head to the body. Then the skull cap to the head. Then the hair to the skull cap.

I cringed at each step. Each wedged in piece. Each weird space. Rosalinda did not look like the doll I’d received all those Christmases ago. Her face was lined with cracks, chips and pits. Her eyes weren’t quite aligned. A large swathe of her forehead was bumpy air dried clay rather than smooth, flesh-toned bisque she started with. She was a mess.

Jovie asked that I paint her so she looked like she did before. But I knew that she was never going to be the doll she was before. I think Jovie hoped that if and when my parents did see Rosalinda again, that maybe they wouldn’t notice she had broken. She worried they would be upset with me. At the very least disappointed. And maybe they would be. Maybe they would be aghast to know I brought Rosalinda to school and then turned my dining room table into a doll hospital and the top of the refrigerator into an ICU. Maybe they would think I didn’t value her enough.

But I know the truth.

The truth is, I didn’t really value Rosalinda when I first received her decades ago. I knew she was valuable. And I appreciated the gesture, but she was just this cumbersome object I was meant to move around from place to place for the rest of my life. Bulky, delicate, old, and expensive.

I didn’t start to value Rosalinda until we made Rosalinda a part of our family’s story. And that meant taking her out of her case from time to time. Dressing her up in a Hawaiian shirt or posing her for pictures at a baby-sized baby grand piano or asking 23 dubious middle schoolers to write scary stories about her.

It turned out that making her less precious only increased her value. And that became no more clear than when she was lying in pieces on a classroom floor.

Rosalinda would never be the same again. So rather than attempt to cover her blemishes, I decided to embrace them. Years ago, I read about Kintsugi* – the Japanese art of fixing broken pottery by filling in the seams with lacquer flaked with gold, silver or platinum. Rather than being camouflaged, the fractures were highlighted. Rather than disguising that something was broken, it’s celebrated. I performed my own amateur kintsugi on Rosalinda, painting all her broke edges with gold. Allowing her to tell a new story. Reminding all of us that nothing is ever so broken it can’t be mended. Reminding us all that broken things are beautiful in their own way.

Twenty years ago when they were wandering around another antique store, I doubt my parents could’ve predicted the lessons an old doll would one day teach me.

Spooked by everyone’s insistence that she was for sure haunted, I started talking to her periodically, just to let her know I saw her and that she was welcome in our home, figuring kindness could neutralize any bad juju (just in case). And how that practice in small conversation, everyday kindness with the things that disturb or unsettle me has made it easier to transfer to overlooked humans who need everyday kindness. She reminds me to look for beauty in unlikely places.

She’s also helped me worry less about what everyone thinks. Moving a giant, possibly haunted doll from house to house over the years has invited plenty of jokes about how she’s weird and how I’m weird for having her and how our whole family by extension is weird for displaying her. Rosalinda taught me it’s empowering to be in on the joke. It’s a joy to be weird.

And when she shattered and Jovie insisted I try to put her back together, she taught me that all you have to do is fit one piece to the next piece and then give them time to dry. Just slowly. Just one thing at a time. Just patience and perseverance.

She taught me that you can love the new thing even more than the old thing because of that process. Because now you know how the body comes together; now you know how to attach the eyes so they open and shut just like they did before; now you know it better.

I thought about this during a recent visit with my parents. A visit I fretted about because our relationship has felt so fractured this past year. Rosalinda sat at the top of the stairs in her usual spot. Her face lined in gold. Obviously damaged.

I wasn’t ready to tell them what happened. I’ll probably never be ready. Instead, I brought Dad to the kitchen. “I have to show you something!” I told him, gesturing toward the tender green spike shooting off the phalaenopsis I’d managed to keep alive for the past 18 months. In addition to being a woodworker and connoisseur of finer things, dad had been a lifelong orchid grower. I’d been gifted this plant at a bridal shower and entertained no thoughts that it might ever bloom again after the last creamy blossoms dropped last year. I was not my father with his green thumb and grow lights and humidity control. Yet there growing in the confines of my humble kitchen- my plant with its healthy roots and happy leaves. The possibility of flowers.

Dad smiled at my little sprout. And we spent an hour talking about everything from orchids to basket weaving to TikTok.

And when they left I breathed a deep sigh of relief, because I never know how it’s going to go. “That was a good visit,” I told Brad.

One more piece attached to the other. Now it just needs time.

And as I consider this, and Rosalinda, and Jovie’s insistence that I just need to try, I remembered a lesson I’ve had to learn over and over. Hope isn’t some delicate, celestial orb forever in danger of shattering. Hope is what comes after the breaking. It’s roughshod and earthy. The work of unsure hands and a hesitating heart. World-weary enough not to make any promises, but unwilling to let die what’s left of the flames.

***

*Speaking of strange magic, I’m reading “Broken (In the Best Possible Way)” by Jenny Lawson. The other night as I was debating whether or not to post this essay, Lawson described breaking a ceramic bird in her kitchen and how sad she felt about it and how her husband suggested she could kintsugi it back together. And I couldn’t decide whether this was a sign that I should hit publish (because how weird it was that complete strangers who are also both long-winded writers came to the same conclusion about our broken treasures years and thousands of miles apart?) or a sign that I should not publish (because, for one, I’ve written about kintsugi (also called kintsukori) before, and for two, evidently it’s not all that original of a metaphor what with the fact that a much more notable and successful writer had already written about it in her much more notable and successful essay). But then, considering this is a centuries-old practice, neither of us are actually all that original so maybe I shouldn’t overthink it.

Life on repeat…. we are all a kaleidoscope pieces, floating around. But, when we look, and we move it all around, the beauty of all those shattered sizes and colors abound! It was my heart felt pleasure to finally meet you this October. Our meeting was at a very precious kaleidoscope moment. Much love, Diane Waller Munnett.

Of course I feel all of this. Sometimes things need to steep for a while, for the flavor to deepen and the edges to soften. I think your written word ( spoken word, texted word) is an addiction for me. I love You.